While many associate Halloween with spine-tingling tales and hair-raising haunts, fear isn't just a once-a-year affair. It's a deeply embedded part of global pop culture, stretching beyond October's eerie ambiance. Not just the stuff of horror films, haunted houses or ghost stories, fear has long been a motivator, urging us into action. So, it was only a matter of time before this primal emotion was harnessed by advertisers and became a powerful, albeit chilling, tool in their arsenal.

Wave I: The Dawn of Fearful Advertising (and Modern Hygiene)

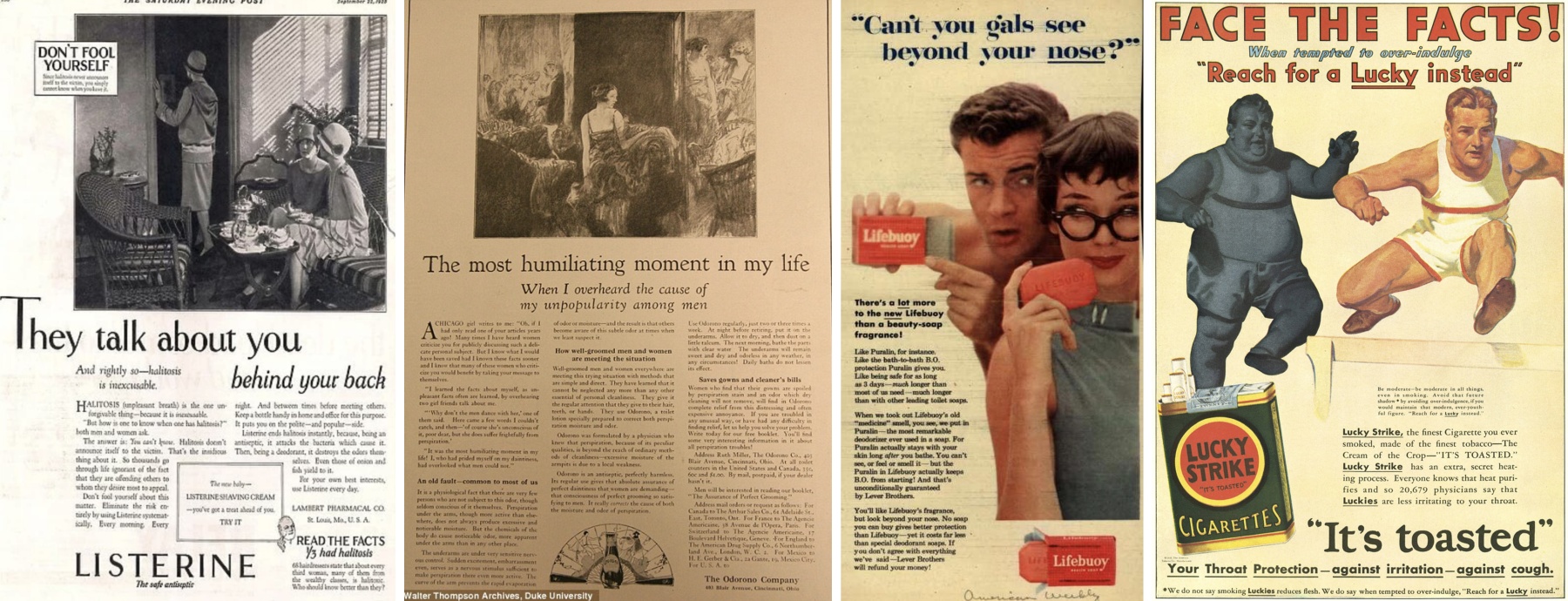

I bet being a woman between 1920s to 1950s was difficult. No, not because of the two world wars, or the lack of rights, or the general misogyny, but because of all these damn new hygiene products. Whereas before taking a bath once a week was plenty, now you must use all these products to hide your B.O. or end up alone.

- If you don’t use Listerine you can end up with the scary sounding Halitosis and your bad breath will end up becoming the talk of the town.

- If you don’t use Odorono’s deodorant men will think you stink, and you will end up alone.

- Without Lifebuoy soap men will also not like you, because you stink, so you will die alone.

- Men had to face similar messaging with Lucky Strike, though to a lesser extent.

Fearmongering targeting vanity and social norms this overt may seem incredibly outlandish to us. Nevertheless, the art of scaring women into buying soap is deeper than it seems, as it targeted (most likely unconsciously) the broader anxieties of the times. The transition from industrial to a more large-scale corporate economic system in 1920s meant that conformity became a valued characteristic in the workforce. The Great Depression also had a conservative impact on society, as people learned the importance economic and social security for survival. Additionally, the Red Scare and growing racial tensions exacerbated the fear of ‘otherness’.

Thankfully, this social climate didn’t last forever: enter 1960s counterculture and the rise of social individualism. Social ostracisation was no longer the bogeyman it once was; it became a vestige of Baby Boomer’s parents’ close-mindedness. Thus, the fear parasite had to find a new marketing host.

How Fear Marketing created Monsters through the Decades

Wave II: Haunting PSAs and Cautionary Tales

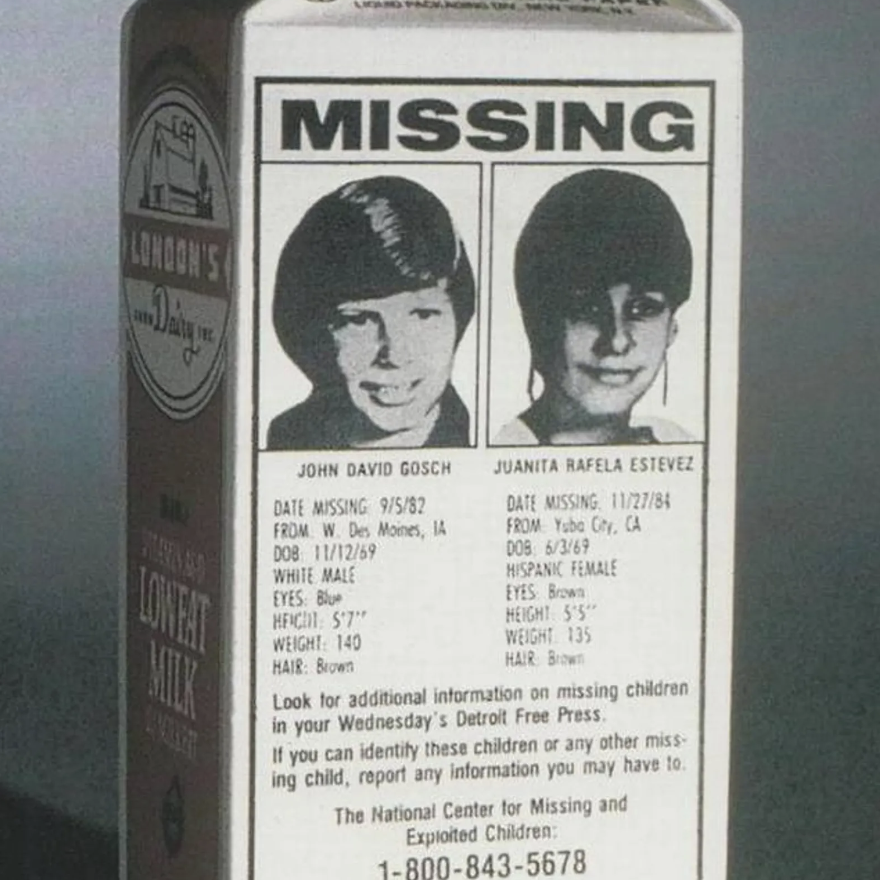

With 1970s came the advent of cable television, flipping the cultural landscape. Suddenly, households were bombarded with contradicting viewpoints, scary news, and captivating ads. Media literacy was not as developed as it is now (even though calling it developed now is a stretch), making the population vulnerable to moral panics. Weed, The Satanic Panic, Stranger Danger, Aids crisis, “Gangsta Rap” – all these

Drenched in gore, hyperbole, and emotional manipulation, these broadcasts overexaggerated threats or created new ones all together.

Wave III: Navigating the Age of Anxiety

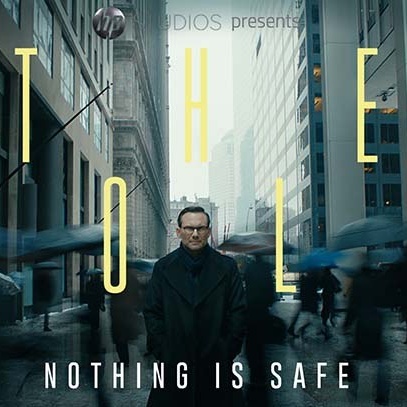

We finally reached the 2010s and the age of anxiety is upon us – marketing and media campaigns have seeped into every nook of our digital lives. Now simply turning off your TV does not stop the dread of the vicious news cycle and our modern fears are more omnipresent and incomprehensible than ever: contamination of our food and water sources, economic collapse, nuclear war, cyber-terrorism. And so, the industries that can use this overwhelming feeling of unease do.

Cybersecurity

firms exploit our lack of privacy, anti-ageing skincare play on our fear of passing time, organic brands

challenge the safety of conventional produce, and AI software

tap into existential concerns about human obsolescence.

They target our lack of expertise in these complex scientific fields, leveraging fear and trust to sell products that might protect us against these eldritch threats.

Decades of such fear-driven strategies have indelibly shaped the public's psyche, often leaving a sense of helplessness in its wake. This Halloween, as we revel in seasonal spooks, let's also remember the subtler, more persistent fears that marketing has often whispered in our ears.

Author is WMH&I creative researcher, Alice Pukhova. The article first featured in Mediashotz.